A retirement plan rollover can be a great thing most of the time. There are a lot of pros — organization, flexibility, more control over your finances — but depending on your individual situation, a rollover could come with some unintentional drawbacks.

Are you planning to keep working into your 70s? Do you prefer to enjoy early retirement? What if you’re employed by the government? We’ll explore these scenarios and more to help you determine if a rollover is the right move for you or if you should hold off.

First things first.

If you’re reading this, presumably you’re already aware of the concept behind rolling over a retirement plan, but if not — here’s a great guide to rollovers and how they work.

Once you understand what your options are, here are some reasons you might not want to move forward with a rollover.

You’re in the sweet spot…

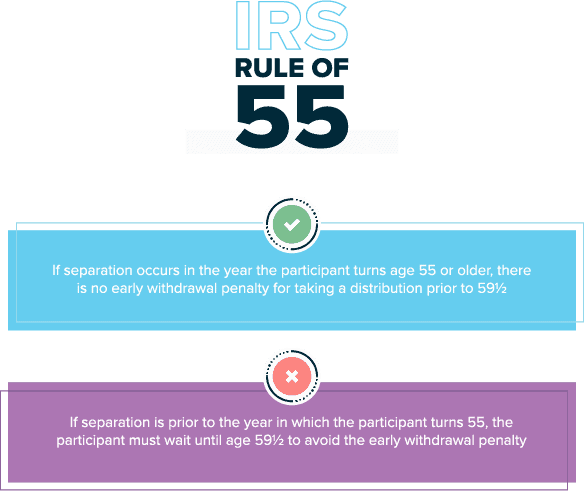

The Rule of 55 is a good concept to know if you’re planning on retiring before age 59½, but it also applies to anyone laid off or let go from a job. To qualify, the separation event must take place in or after the year you turn 55.

The Rule of 55 allows access to retirement funds with no early withdrawal penalties for 401(k) and 403(b) plans.

However, you can only take advantage of the strategy using funds from your most recent employer-sponsored retirement plan. You’ll still be penalized for early withdrawals if you try to take money out of any old 401(k) or 403(b) plan.

If you’re considering this path, be aware of certain things you’ll have to plan for, including a fairly specific timeframe. If working with an advisor, he/she can help you navigate this and take the pressure off managing it on your own.

You’ve got a state-sponsored retirement plan.

This one technically has more to do with pension plans than 401(k)s, but it’s still an important example of when to think twice about a retirement plan rollover.

If you’re employed by a state or local government, “defined-benefit plan” probably rings a bell. Or perhaps you know it simply as a “pension plan.”

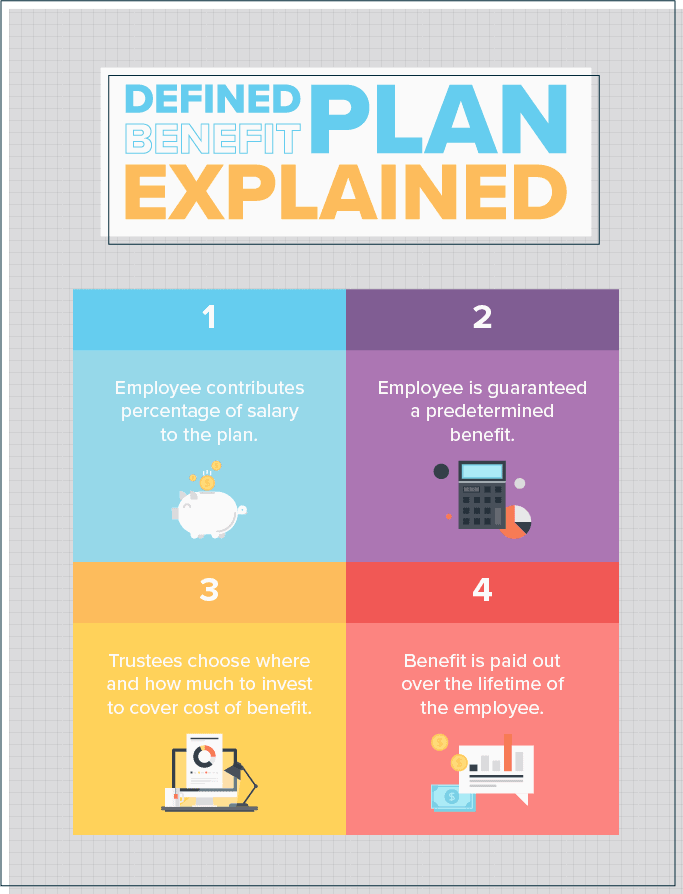

A defined-benefit plan is an employer-sponsored retirement plan where employee benefits are computed using a formula that considers several factors, such as length of employment and salary history.

It’s “defined” because employers and employees know ahead of time what the formula is for calculating retirement benefits. Both parties use that formula to define and set the benefit pay-out accordingly.

The catch?

The benefit formula can work to your disadvantage if you blindly rollover your 401(k) after a separation event. There are some additional questions you want to ask first before making a decision.

Is there ever a chance you could go back to work for this entity? If you’re a public school or university teacher — are you transferring to another public school or university in another city or state? Will they accept your transfer credits?

If you answer “yes” or even “maybe” — you might want to hold off on the rollover for now.

Rolling over funds prematurely could put you at a disadvantage if you ever decide to go back to work for an entity that uses the same retirement system.

Sure, you can always “buy back” your time or years of service. But as an advisor can quickly show you, this very rarely makes financial sense.

You’re working past age 72.

With most Americans now expecting to work into their 70s, this next scenario could prove to be an important one. No fancy term needed — this is the “still-working exception.”

Normally, once you hit age 72, the IRS requires you to take certain minimum withdrawals from your pre-tax retirement accounts. If you’re still working, you can defer your required distributions. This is called a required minimum distribution (RMD). This is a great reason to hold off on rolling over that 401(k).

Like most money-savvy moves, this exception isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. For example, there are certain “traps” that could get you if you don’t technically work long enough or you own too much stock in the company.

It also only applies to the retirement plan you have through your current employer. It does not apply to old employer-sponsored plans or outside IRAs.

Working with an advisor will help you avoid these traps, calculate your required withdrawals, and keep you on track with your saving.

You’re leveraging a backdoor Roth IRA.

This tends to be a favorite tool of high earners. Backdoor Roth IRAs allow you to continue contributing to Roth IRAs even if your income exceeds the modified adjusted gross income limits.

When it comes to rolling your funds over, however, the way these accounts are taxed can be a disadvantage.

Essentially, if you have any retirement funds outside of an employer-sponsored account (like an IRA), the balance of those accounts could negatively affect your tax liability for the backdoor Roth IRA.

We’ll try to break this down. Buckle up – it’s going to get bumpy.

A Perfect-World Scenario:

A high-income earner would contribute to a non-deductible traditional IRA and then immediately convert that contribution to a Roth IRA. If said earner had no other pre-tax accounts outside of his/her employer-sponsored plan, he/she would be able to make this conversion with no tax liability at all.

So what does a less than perfect scenario look like?

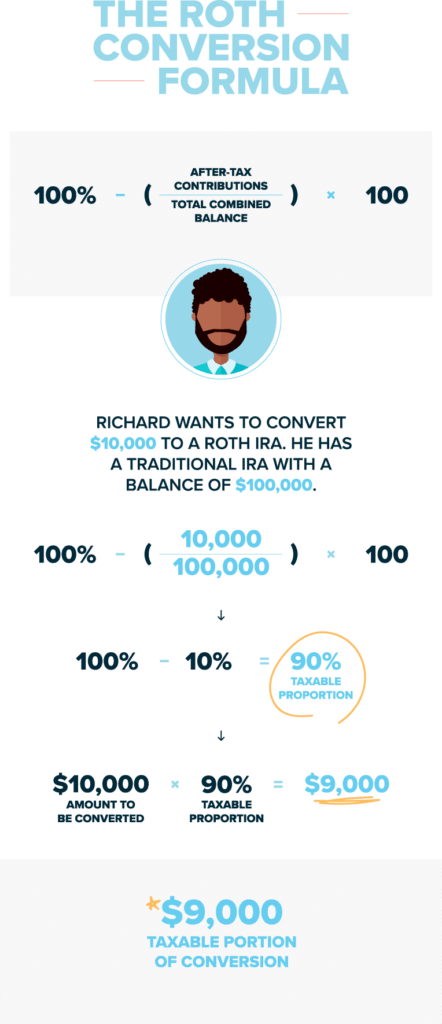

Here’s where it could get a little more complicated: if our high-income earner did have pre-tax accounts outside of his/her employer-sponsored plan. In this scenario, the IRS has a very specific formula for calculating what percentage of your pre-tax balance you have to pay taxes on in order to successfully convert the money from pre- to post-tax. This formula takes into account all of your pre-tax accounts (even SEP and SIMPLE IRAs) but excludes any employer-sponsored retirement plans such as 401(k)s from the calculation.

This means that the more you have in pre-tax accounts outside of your employer-sponsored plan, the more you’re likely to pay in taxes if you choose to convert a portion of it to post-tax via the backdoor Roth conversion strategy.

Since you’re likely in a pretty high tax bracket if you’re leveraging a backdoor Roth, keep in mind that you can also spread your conversions out over several years in order to minimize your tax liability. This is a great option if you have a large pre-tax balance that you’d like to convert to post-tax.

So, again — a lot to think about. Investopedia offers another helpful breakdown, special considerations, and tax implications if you’re considering leveraging this strategy. An advisor can also help you work through the calculations and determine how a rollover would fit into your overall plan.

The Bottom Line

Not all these situations are applicable to everyone. There’s no straight yes or no answer to whether to do a retirement plan rollover or not. There are times where a rollover might make sense for you, but not necessarily for your coworker — or vice-versa. This is okay.

As with any financial planning strategy, the devil is in the details with these (or other) rollover exceptions. You definitely want to make sure you fully understand your options. Better yet, work with an advisor who can walk you through specifics and help you uncover the best path forward.

You can fill out a form or give us a call, and we’ll guide you through the best strategy for your individual situation.

The information in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only, and should not be construed as investment, tax, or other financial planning advice.